A few weeks ago, I released http://removephotodata.com as a tool. It is a simple web app (well, a page) that allows you to remove the EXIF data of an image before sharing it online. I created it as a companion to my “Put social back in social media” talk at TEDx Linz. During this talk I pointed out the excellent exiftool. A command line tool to remove extra information embedded in images people might not want to share. As such, it is too hard to use for most users. So I thought this would be a good solution.

It had some success and people – including the press in Spain – talked about it. Without fail though, every thread of comments or Twitter conversation will have one person pointing out the “seemingly obvious”:

So you create a tool to remove personal data from images and to do that I need to send the photo to your server! FAIL! LOLZ0RZ (and similar)

Which is not true at all. The only server interaction needed is the first load of the page. All the JavaScript analysis and removal of EXIF data happens on your computer. I even added a appcache to ensure that the tool itself works offline. In essence, everything happens on your computer or smartphone. This makes a lot of sense – it would be nonsense to use a service on some machine to remove personal data for you.

I did explain this in the page:

Your photo does not get uploaded anywhere, all of this happens on your device, in your browser. It even works offline.

Nobody seems to read that, though and it is quicker to complain about a seemingly non-sensical security tool.

This is not the user’s fault, it is conditioning. We’ve so far have done a bad job advocating the need for offline functionality. The web is an online medium. It’s understandable that people don’t expect a browser to work without an internet connection.

Apps, on the other hand, are expected to work offline. This, of course, is nonsense. The sad state of affairs is that most apps do not work offline. Look around on a train when people are not connected. You see almost everyone on their phone either listening to local music, reading books or playing games. Games are the only things that work offline. All other apps are just sitting there until you connect. You can’t even write your posts as drafts in most of them – something any email client was able to do a long time ago.

People also seem to trust native apps more as they are on your device. You have to go through an install and uninstall process to get them. You see them downloading and installing. Web Apps arrive by magic. This is less re-assuring.

This is security by obscurity and thus to me more dangerous. Of course it is good to know when something gets to your computer. But an install process gives the app more rights to do things, it doesn’t necessarily mean that software is more secure.

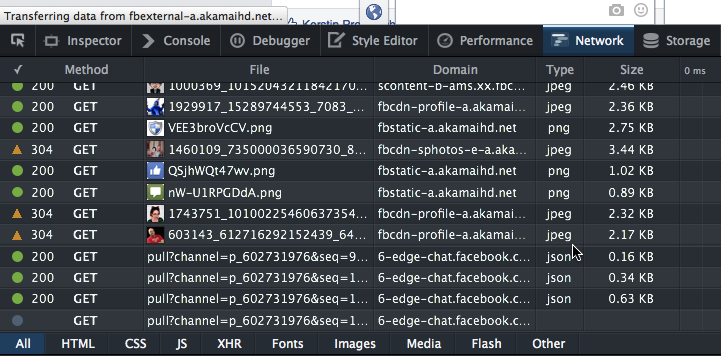

Native apps don’t give us more security or insight into what is going on – on the contrary. A packaged format with no indicator when the app is sending or receiving data from the web allows me to hide a lot more nasties than a web site could. It is pretty simple with developer tools in a browser to see what is going on:

On my mobile, I have to hope that the Android game doesn’t call home in the background. And I should read the terms and conditions and understand the access the game has to my device. But, no, I didn’t read that and just skimmed through the access rights and ticked “yes” as I wanted to play that game.

There is no doubt that JavaScript in browsers has massive security issues. But it isn’t worse or better than any other of the newer languages. When Richard Stallman demonised JavaScript as a trap as you run code that might not be open on your computer he was right. He was also naive in thinking that people cared about that. We live in a world where we give away privacy and security for convenience. That’s the issue we need to address. Not if you could read all the code that is on your device. Only a small amount of people on this world can make sense of that anyways.

There is great work in the making towards an offline web. Google’s and Mozilla’s ServiceWorker implementations are going places. The latest changes in Chrome give the browser on the device much more power to store things offline. IndexedDB, WebSQL and other local storage solutions are available across browsers. Web Cryptography is coming. Tim Taubert gave an interesting talk about this at JSConf called “Keeping secrets with JavaScript: An Introduction to the WebCrypto API“.

The problem is that we also need to create a craving in our users to have that kind of functionality. And that’s where we don’t do well.

There is no indicator in the browser that something works offline. We need to tell the user in our copy or with non-standardised icons. That’s not good. We assume a lot from our users when we do that.

When we started offering offline functionality with appcache we did an even worse job. We warned users that the site is trying to store information on their device. In essence we conditioned our users to not trust things that come from the web – even if they requested that data.

Offline functionality is a must. The wonderful world of constant, free and fast connectivity only exists in movies and advertisements for mobiles and smart devices. This is not going to happen any time soon as physics is not likely to change and replacing a lot of copper cable in the ground is quite a job.

We also need to advocate better that users have a right to use their devices offline. Mobile phones are multi-processor machines with a lot of RAM and storage. Why not use that? Why would I have to store my information in the cloud for everything I do? Can I trust the cloud? What is the cloud? To me, it is “someone else’s computer” and they have the right to analyse my data, read it and even cut me off from it once their first few rounds of funding money runs out. My phone I got, why can’t I do more with it when I am offline? Why can’t I sync data with a USB cable?

Of course, all of this is about convenience. It is easier to have my data synced across devices with a cloud service. That way I never lose anything – if the cloud provider is OK with me getting to my data.

Our devices are powerful machines and we should be able to create, encrypt and store information without someone online snooping on me doing it. For this to happen, we need to create users that are aware of these options and see them as a value-add. It is not an easy job – the marketing around the simplicity of closed systems with own cloud services is excellent. But so are we, aren’t we?