Since Brendan Eich wrote the first SpiderMonkey version in 1995, there have been many, many changes to its internal string representation. New string types like inline strings (more on this below) and ropes were added to save memory and improve performance, but the character representation never changed: string characters were always stored as . The past two months I’ve been working on changing this. The JS engine can now store Latin1 strings (strings that only use the first 256 Unicode code points) more efficiently: it will use 1 byte per character instead of 2 bytes. This is purely an internal optimization, JS code will behave exactly the same. In this post I will use the term Latin1 for the new 8-bit representation and TwoByte for the 16-bit format.

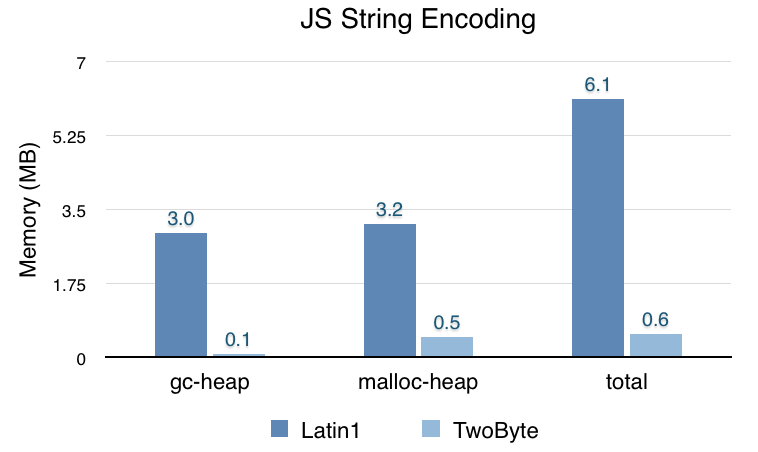

To measure how much memory this saves, I opened Gmail, waited 15 seconds then opened about:memory and looked at the zones/strings subtree under “Other measurements”:

For every JS string we allocate a small, fixed-size structure (JSString) on the gc-heap. Short strings can store their characters inline (see the Inline strings section below), longer strings contain a pointer to characters stored on the malloc-heap.

Note that the malloc-heap size was more than halved and the total string memory was reduced by about 4 MB (40%). The difference between 32-bit and 64-bit is pretty small, JSString is 16 bytes on 32-bit and 24 bytes on 64-bit, but on 64-bit it can store more characters inline.

The chart below shows how much of our string memory is used for Latin1 strings vs TwoByte strings on 64-bit:

Almost all strings are stored as Latin1. As we will see below, this is also the case for non-Western languages. The graph suggests some longer strings (that use malloc storage) are still stored as TwoByte. Some of these strings are really TwoByte and there’s not much we can do there, but a lot of them could be stored as Latin1. There are follow-up bugs on file to use Latin1 strings in more cases.

Why not use UTF8?

At this point you may ask: wait, it’s 2014, why use Latin1 and not UTF8? It’s a good question and I did consider UTF8, but it has a number of disadvantages for us, most importantly:

- Gecko is huge and it uses TwoByte strings in most places. Converting all of Gecko to use UTF8 strings is a much bigger project and has its own risks. As described below, we currently inflate Latin1 strings to TwoByte Gecko strings and that was also a potential performance risk, but inflating Latin1 is much faster than inflating UTF8.

- Linear-time indexing: operations like charAt require character indexing to be fast. We discussed solving this by adding a special flag to indicate all characters in the string are ASCII, so that we can still use O(1) indexing in this case. This scheme will only work for ASCII strings, though, so it’s a potential performance risk. An alternative is to have such operations inflate the string from UTF8 to TwoByte, but that’s also not ideal.

- Converting SpiderMonkey’s own string algorithms to work on UTF8 would require a lot more work. This includes changing the irregexp regular expression engine we imported from V8 a few months ago (it already had code to handle Latin1 strings).

So although UTF8 has advantages, with Latin1 I was able to get significant wins in a much shorter time, without the potential performance risks. Also, with all the refactoring I did we’re now in a much better place to add UTF8 in the future, if Gecko ever decides to switch.

Non-Western languages

So Latin1 strings save memory, but what about non-Western languages with non-Latin1 characters? It turns out that such websites still use a lot of Latin1 strings for property names, DOM strings and other identifiers. Also, Firefox and Firefox OS have a lot of internal JS code that’s exactly the same for each locale.

To verify this, I opened the top 10 most popular Chinese websites, then looked at about:memory. 28% of all strings were TwoByte, this is definitely more than I saw on English language websites, but the majority of strings were still Latin1.

String changes

Each JSString used to have a single word that stored both the length (28 bits) and the flags (4 bits). We really needed these 4 flag bits to encode all our string types, but we also needed a new Latin1 flag, to indicate the characters are stored as Latin1 instead of TwoByte. I fixed this by eliminating the character pointer for inline strings, so that we could store the string length and flags in two separate 32-bit fields. Having 32 flags available meant I could clean up the type encoding and make some type tests a lot faster. This change also allowed us to shrink JSString from 4 words to 3 words on 64-bit (JSString is still 4 words on 32-bit).

After this, I had to convert all places where SpiderMonkey and Gecko work with string characters. In SpiderMonkey itself, I used C++ templates to make most functions work on both character types without code duplication. The deprecated HTML string extensions were rewritten in self-hosted JS, so that they automatically worked with Latin1 strings.

Some operations like eval currently inflate Latin1 to a temporary TwoByte buffer, because the parser still works on TwoByte strings and making it work on Latin1 would be a pretty big change. Fortunately, as far as I know this did not regress performance on any benchmarks or apps/games. The JSON parser, regex parser and almost all string functions can work on Latin1 strings without inflating.

When I started working on this, Terrence mentioned that if we are going to refactor our string code, it’d be good to make all string code work with unstable string characters as well: once we start allocating strings in the GGC nursery (or have compacting GC for strings), we can no longer hold a pointer to string characters across a GC, because the GC can move the characters in memory, leaving us with a dangling pointer. I added new APIs and functions to safely access string characters and pave the way for more string improvements in the future.

After converting all of SpiderMonkey’s string code, I had to make Gecko work with Latin1 JS strings and unstable string characters. Gecko has its own TwoByte string types and in many cases it used to avoid copying the JS characters by using a nsDependentString. This is not compatible with both Latin1 strings and nursery allocated strings, so I ended up copying (and inflating) JS strings when passing them to Gecko to solve both problems. For short strings we can use inline storage to avoid malloc or nsStringBuffer and overall this turned out to be fast enough: although it was about 10% slower on (pretty worst-case) getAttribute micro-benchmarks, none of our DOM benchmarks noticeably regressed as far as I know. For longer strings, the copy is potentially more expensive, but because I used a (refcounted) nsStringBuffer for those, it often avoids copying later on.

Inline strings

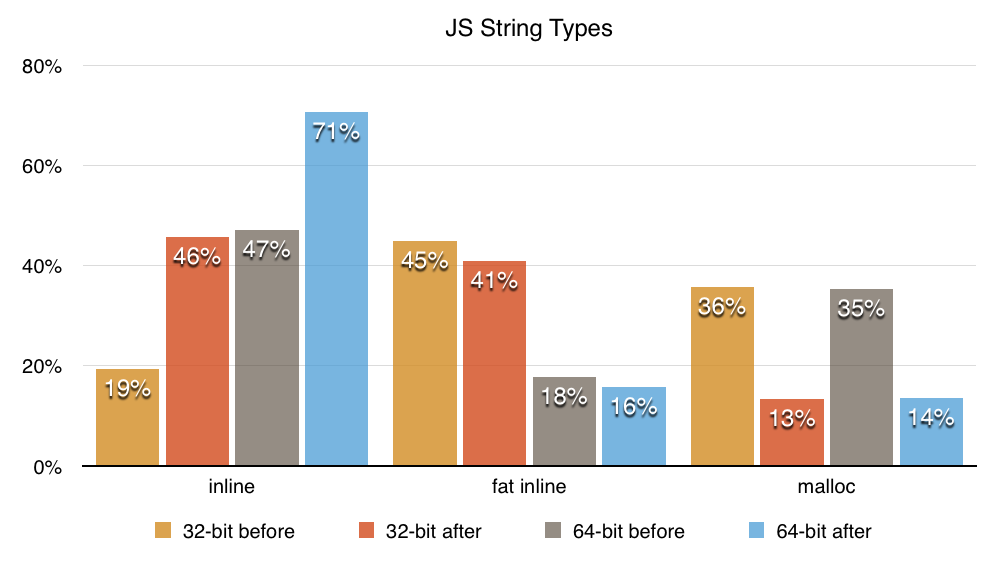

SpiderMonkey has two string types that can store their characters inline, instead of on the malloc heap: inline strings (size of a normal JSString) and fat inline strings (a few words bigger than a JSString). The table below shows the number of characters they can store inline (excluding the null terminator):

| 32-bit Latin1 | 32-bit TwoByte | 64-bit Latin1 | 64-bit TwoByte | |

| Inline | 7 | 3 | 15 | 7 |

| Fat inline | 23 | 11 | 23 | 11 |

So a Latin1 string of length 15 can be stored in an inline string on 64-bit and a fat inline string on 32-bit. Latin1 strings can store more characters inline so, as expected, there are a lot more inline strings now (measured after opening Gmail):

87% of strings can store their characters inline, this used to be 65%. Inline strings are nice for cache locality, save memory and improve performance (malloc and free are relatively slow). Especially on 64-bit, non-fat inline strings are now more common than fat inline strings, because most strings are very short.

These numbers include atoms, a string subtype the engine uses for property names, identifiers and some other strings. Minimized JS code is likely responsible for many short strings/atoms.

Note that SpiderMonkey has other string types (ropes, dependent strings, external strings, extensible strings), but more than 95% of all strings are inline, fat inline or malloc’ed so I decided to focus on those to avoid making the chart more complicated.

Performance

The main goal was saving memory, but Latin1 strings also improved performance on several benchmarks. There was about a 36% win on Sunspider regexp-dna on x86 and x64 on AWFY (the regular expression engine can generate more efficient code for Latin1 strings) and a 48% win on Android.

There were also smaller wins on several other benchmarks, for instance the Kraken JSON tests improved by 11% on x86 and x64. On ARM this was closer to 20%.

Conclusion

Latin1 strings are in Firefox Nightly, will be in Aurora this week and should ship in Firefox 33. This work also paves the way for generational and compacting GC for strings, I’ll hopefully have time to work on that in the coming weeks. Last but not least, I want to thank Luke Wagner, Terrence Cole, Nicholas Nethercote, Boris Zbarsky, Brian Hackett, Jeff Walden and Bobby Holley for many excellent and fast reviews.