Functional programming has been on the rise the last few years. Languages such as Clojure, Scala and Haskell have brought to the eyes of imperative programmers interesting techniques that can provide significant benefits in certain use cases. Immutable.js aims to bring some of these benefits to JavaScript in an easy and intuitive API. Follow us through this overview to learn some of these benefits and how to make them count in your projects!

Introduction: the case for immutability and Immutable.js

Although functional programming is much more than just immutability, many functional languages put a strong emphasis on immutability. Some, like Clean and Haskell, place hard compile-time restrictions on how and when data can be mutated. Many developers are put off by this. For those who endure the initial shock, new patterns and ways of solving problems begin to arise. In particular, data structures are a major point of conflict for newcomers to the functional paradigm.

In the end, the matter of immutable vs mutable data structures comes down to cold, hard math. Algorithmic analysis tells us which data structures are best suited for different kinds of problems. Language support, however, can go a long way into helping with the use and implementation of those data structures. JavaScript, by virtue of being a multi-paradigm language, provides a fertile ground for both mutable and immutable data structures. Other languages, such as C, can implement immutable data structures. However, the limitations of the language can make their use cumbersome.

So what is a mutation exactly? Mutations are in-place changes to data or the data structures that contain it. Immutability on the other hand, makes a copy of such data and data structures whenever a change is required.

Image taken from Wikipedia.

So what are the tenets of functional data structures, and, in particular what makes immutability so important? Furthermore, what are the right use cases for them? These are some of the questions we will explore below.

Note: you may not know this, but you may already be using certain functional programming constructs in your JavaScript code. For instance,

Array.mapapplies a function to each item in an array and returns a new array, without modifying the original in the process. Functional programming as a paradigm favors first-class functions that can be passed to algorithms returning new versions of existing data. This is in fact whatArray.mapdoes. This way of processing data favors composition, another core concept in functional programming.

Key Concepts

These are some of the key concepts behind functional programming. Hopefully, throughout this post you will find how these concepts fit in the design and use of Immutable.js and other functional libraries.

Immutability

Immutability refers to the way data (and the data structures managing it) behave after being instanced: no mutations are allowed. In practice, mutations can be split in two groups: visible mutations and invisible mutations. Visible mutations are those that either modify the data or the data structure that contains it in a way that can be noted by outside observers through the API. Invisible mutations on the other hand, are changes that cannot be noted through the API (caching data structures are a good example of this). In a sense, invisible mutations can be considered side-effects (we explore this concept and what it means below). Immutability in the context of functional programming usually forbids any of these two modifications: not only is data immutable by default, but the data structures themselves suffer no changes once instanced.

var list1 = Immutable.List.of(1, 2);

// We need to capture the result through the return value:

// list1 is not modified!

var list2 = list1.push(3, 4, 5);

Interesting benefits arise when developers (and compilers/runtimes) can be sure data cannot change:

- Locking for multithreading is no longer a problem: as data cannot change, no locks are needed to synchronize multiple threads.

- Persistence (another key concept explored below) becomes easier.

- Copying becomes a constant-time operation: copying is simply a matter of creating a new reference to the existing instance of a data structure.

- Value comparisons can be optimized in certain cases: when the runtime or compiler can make sure during loading or compiling that a certain instance is only equal when pointing to the same reference, deep value comparisons can become reference comparisons. This is known as interning and is normally only available for data available at compile or load time. This optimization can also be performed manually (as is done with React and Angular, explained in the aside section at the end).

You are already using an immutable data structure: strings

Strings in JavaScript are immutable. All methods in the String prototype perform either read operations or return new strings.

Some JavaScript runtimes take advantage of this to perform interning: at load time or during JIT compilation the runtime can simplify string comparisons (usually between string literals) to simple reference comparisons. You can check how your browser handles this with a simple JSPerf test case. Check other revisions of the same test for more thorough test cases.

Immutability and Object.freeze()

JavaScript is a dynamic, weakly typed language (or untyped if you're familiar with programming language theory). As such it is sometimes hard to enforce certain constraints on objects and data. Object.freeze() helps in this regard. A call to Object.freeze marks all properties as immutable. Assignments will either silently fail or throw an exception (in strict mode). If you are writing an immutable object, calling Object.freeze after construction can help.

Bear in mind Object.freeze() is shallow: attributes of child objects can be modified. To fix this, Mozilla shows how a deepFreeze version of this function can be written:

function deepFreeze(obj) {

// Retrieve the property names defined on obj

var propNames = Object.getOwnPropertyNames(obj);

// Freeze properties before freezing self

propNames.forEach(function(name) {

var prop = obj[name];

// Freeze prop if it is an object

if (typeof prop == 'object' && prop !== null) {

deepFreeze(prop);

}

});

// Freeze self (no-op if already frozen)

return Object.freeze(obj);

}

Side-effects

In programming language theory, side-effects to any operation (usually a function or method call) are observable effects that can be seen outside the call to the function. In other words, it is possible to find a change in state after the call is performed. Each call mutates some state. In contrast to the concept of immutability, which is usually related to data and data structures, side-effects are usually associated to the state of a program as a whole. A function that preserves immutability of an instance of a data structure can have side-effects. A good example of this are caching functions, or memoization. Although to outside observers it may look like no change has occurred, updating a global or local cache has the side-effect of updating the internal data structures that work as the cache (the resulting speedups are also a side-effect). It is the job of developers to be aware of those side-effects and handle them appropriately.

For instance, following the example of the cache, an immutable data structure that has a cache as a frontend can no longer be freely passed to different threads. Either the cache has to support multithreading or unexpected results can happen.

Functional programming as a paradigm favors the use of side-effect free functions. For this to apply, functions must only perform operations on the data that is passed to them, and the effects of those operations should only be seen to the callee. Immutable data structures go hand-in-hand with side-effect free functions.

var globalCounter = 99;

// This function changes global state.

function add(a, b) {

++globalCounter;

return a + b;

}

// A call to the seemingly innocent add function above will produce potentially

// unexpected changes in what is printed in the console here.

function printCounter() {

console.log(globalCounter.toString());

}

Purity

Purity is an additional condition that may be imposed on functions: pure functions rely only on what is explicitly passed to them as arguments to produce a result. In other words, pure functions must not rely on global state or state accessible through other constructs.

var globalValue = 99;

// This function is impure: its result will change if globalValue is changed,

// even when passed the same values in 'a' and 'b' as in previous calls.

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b + globalValue;

}

Referential transparency

The result of combining side-effect free functions with purity is referential transparency. A referentially transparent function passed the same set of parameters can be replaced at any point by its result knowing for certain this changes in no way the computation as a whole.

As you may have noticed, each of these conditions places higher restrictions on how data and code can behave. Although this results in reduced flexibility, deep gains are realized when it comes to analysis and proofs. It is trivially provable that immutable data structures with no side-effects can be passed to different threads without worrying about locking, for instance.

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

// The following call can be replaced by its result: 3. This is possible because

// it is referentially transparent. IOW, side-effect free and pure.

var r1 = add(1, 2); // r1 = 3;

Persistence

As we have seen in the previous section, immutability makes certain things easier. Another thing that becomes easier with immutable data structures is persistence. Persistence, in the context of data structures, refers to the possibility of keeping older versions of a data structure after a new version is constructed.

As we have mentioned before, when write operations are to be performed on immutable data structures, rather than mutating the structure itself or its data, a new version of the structure is returned. Most of the time, however, modifications are small with regards to the size of the data or the data structure. Performing a full copy of the whole data structure is therefore suboptimal. Most immutable data structure algorithms, taking advantage of the immutability of the first version of the data, perform copies of only the data (and the parts of the data structure) that need to change.

Partially persistent data structures are those which support modifications on its newest version and read-only operations on all previous versions of the data. Fully persistent data structures allow reading and writing on all versions of the data. Note that in all cases, writing or modifying data implies creating a new version of the data structure.

It may not be entirely obvious but persistent data structures favor garbage collection rather than reference counting or manual memory management. As each change results in a new version of the data, and previous versions must be available, each time a change is performed, new references to existing data are created. On manual memory management schemes, keeping track of which pieces of data have references quickly gets troublesome. On the other hand, reference counting makes things easier from the developer point of view, but inefficient from an algorithmic point of view: each time a change is performed, reference counts of changed data must be updated. Furthermore, this invisible change is in truth a side-effect. As such, it limits the applicability of certain benefits. Garbage collection, on the other hand, comes with none of these problems. Adding a reference to existing data comes for free.

In the following example, each version of the original list since its creation is available (through each variable binding):

var list1 = Immutable.List.of(1, 2);

var list2 = list1.push(3, 4, 5);

var list3 = list2.unshift(0);

var list4 = list1.concat(list2, list3);

Lazy evaluation

Another not-so-obvious benefit of immutability comes in the form of easier lazy operations. Lazy operations are those that do not perform any work until the results of those operations are required (usually by a strict evaluating operation; strict being the opposite of lazy in this context). Immutability helps greatly in the context of lazy operations because lazy evaluation usually entails performing an operation in the future. If the data associated to such operation is changed in any way between the time the operation is constructed and its results are required, then the operation cannot be safely performed. Immutable data helps because lazy operations can be constructed being certain data will not change. In other words, immutability enables lazy evaluation as an evaluation strategy.

Lazy operations are supported in Immutable.js:

var oddSquares = Immutable.Seq.of(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)

.filter(x => x % 2)

.map(x => x * x);

// Only performs as much work as necessary to get the first result

console.log(oddSquares.get(1)); // 9

There are several benefits to lazy evaluation. The most important one is that unnecessary values need not be computed. For example, consider a list formed by the elements 1 to 10. Now let's apply two independent operations to each element in the list. The first operation will be called plusOne and the second plusTen. Both operations do what's obvious: the first adds one to its argument, the second adds ten.

function plusOne(n) {

return n + 1;

}

function plusTen(n) {

return n + 10;

}

var list = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10];

var result = list.map(plusOne).map(plusTen);

As you may have noticed, this is inefficient: the loop inside map runs twice even though no elements from result have been used yet. Suppose you only need the first element: with strict evaluation both loops run completely. With lazy evaluation each loop runs until the requested result is returned. In other words, if result[0] is requested, only one call to each plus... function is performed.

Lazy evaluation may also allow for infinite data structures. For instance a sequence from 1 to infinity can be safely expressed if lazy evaluation is supported. Lazy evaluation can also allow for invalid values: if invalid values inside a computation are never requested, then no invalid operations are performed (which may result in exceptions or other error conditions).

Certain functional programming languages can also perform advanced optimizations when lazy evaluation is available, such as deforestation or loop fusion. In essence these optimizations can turn operations defined in terms of multiple loops into single loops, or, in other words, remove intermediate data structures. In practice, the two map calls from the example above turn into a single map call that calls plusOne and plusTen in the same loop. Nifty, huh?

However, not everything is good about lazy evaluation: the exact point at which any expression gets evaluated and a computation performed stops being obvious. Analysis of certain complex lazy operations can be quite hard. Another disadvantage are space-leaks: leaks that result from storing the necessary data to perform a given computation in the future. Certain lazy constructs can make this data grow unbounded, which may result in problems.

Composition

Composition in the context of functional programming refers to the possibility of combining different functions into new powerful functions. First-class functions (functions that can be treated as data and passed to other functions), closures and currying (think of Function.bind on steroids) are the tools necessary for this. JavaScript's syntax is not as convenient as certain functional programming languages' syntax for composition but it certainly is possible. Appropriate API design can produce good results.

Immutable's lazy features combined with composition result in convenient, readable JavaScript code:

Immutable.Range(1, Infinity)

.skip(1000)

.map(n => -n)

.filter(n => n % 2 === 0)

.take(2)

.reduce((r, n) => r * n, 1);

The Escape Hatch: Mutation

For all the advantages immutability can provide, certain operations and algorithms are only efficient when mutation is available. Although immutability is the default in most functional programming languages (in contrast with imperative languages), mutations are usually possible to efficiently implement these operations.

Again, Immutable.js has you covered:

var list1 = Immutable.List.of(1,2,3);

var list2 = list1.withMutations(function (list) {

list.push(4).push(5).push(6);

});

Algorithmic Considerations

In the field of algorithms and data structures there are no free meals. Improvements in one area usually result in worse results in another. Immutability is no exception. We have discussed some of the benefits of immutability: easy persistence, simpler reasoning, less locking, etc.; but what are the disadvantages?

When talking about algorithms, time complexity is probably the first thing you should keep in mind. Immutable data structures have different run-time characteristics than mutable data structures. In particular, immutable data structures usually have good runtime characteristics when taking persistence requirements in consideration.

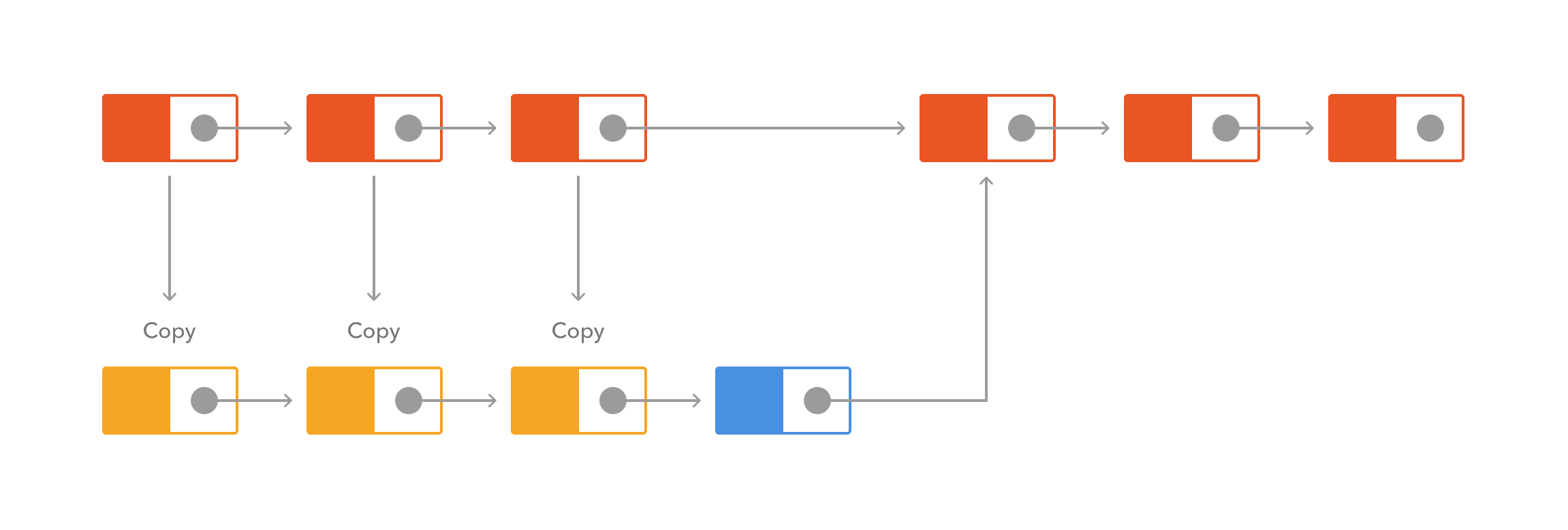

A simple example of these differences are single-linked lists: lists formed by having each node point to the next one (but not back).

Diagram based on Leslie Sanford's Persistent Data Structures diagrams.

A mutable single-linked list has the following time complexities (worst-case, assuming front, back and insertion nodes are known):

- Prepend: O(1)

- Append: O(1)

- Insert: O(1)

- Find: O(n)

- Copy: O(n)

In contrast, an immutable single-linked list has the following time complexities (worst-case, assuming front, back and insertion nodes are known):

- Prepend: O(1)

- Append: O(n)

- Insert: O(n)

- Find: O(n)

- Copy: O(1)

In case you are not familiar with time analysis and Big O notation, read this.

This does not paint a good picture for the immutable data structure. However, worst-case time analysis does not consider the implications for persistent requirements. In other words, if the mutable data structure had to comply with this requirement, run-time complexities would mostly look like those from the immutable version (at least for these operations). Copy-on-write and other techniques may improve average times for some operations, which are also not considered for worst-case analysis.

In practice, worst-case analysis may not always be the most representative form of time analysis for picking a data structure. Amortized analysis considers data structures as a group of operations. Data structures with good amortized times may display occasional worst-time behavior while remaining much better in the general case. A good example where amortized analysis makes sense is a dynamic array optimized to double its size when an element needs to be allocated past its end. Worst-case analysis gives O(n) time for the append operation. Amortized time can be considered O(1), since N/2 append operations can be performed before a single append results in O(n) time. In general, if deterministic times are required for your use case, amortized times cannot be considered. Otherwise, careful analysis of your requirements may give data structures with good amortized times a better chance.

Time complexity analysis leaves out other important considerations as well: how does the use of a certain data structure impact on the code around it? For instance, with an immutable data structure, locking may not be necessary in multi-threaded scenarios.

CPU Cache Considerations

Another thing to keep in mind, in particular for high-performance computing, is the way data structures play with the underlying CPU cache. In general, locality for mutable data structures is better (unless persistence is deeply used) for cases where many write operations are performed.

Memory use

Immutable data structures cause by nature spikes in memory usage. After each modification, copies are performed. If these copies are not required, the garbage collector can collect old pieces of data during the next collection. This results in spikes of usage as long as the old, unused copies of the data are not collected. In the case persistence is required, spikes are not present.

As you may have noticed, immutability becomes pretty compelling when persistence is considered.

Example: React DBMon Benchmark

Based on our previous series of benchmarks, we decided to update our React DBMon benchmark to use Immutable.js where appropriate. As DBMon essentially updates all data after each iteration, no benefits would be gained by switching to React + Immutable.js: Immutable allows React to prevent deep equality checks after the state is changed; if all state is changed after each iteration, no gains are possible. We thus modified our example to randomly skip state changes:

// Skip some updates to test re-render state checks.

var skip = Math.random() >= 0.25;

Object.keys(newData.databases).forEach(function (dbname) {

if (skip) {

return;

}

//(...)

});

After that, we changed the data structure holding the samples from a JavaScript array to an Immutable List. This list is passed as a parameter to a component for rendering. When React's PureRenderMixin is added to the component class, more efficient comparisons are possible.

if (!this.state.databases[dbname]) {

this.state.databases[dbname] = {

name: dbname,

samples: Immutable.List()

};

}

this.state.databases[dbname].samples =

this.state.databases[dbname].samples.push({

time: newData.start_at,

queries: sampleInfo.queries

});

if (this.state.databases[dbname].samples.size > 5) {

this.state.databases[dbname].samples =

this.state.databases[dbname].samples.skip(

this.state.databases[dbname].samples.size - 5);

}

var Database = React.createClass({

displayName: "Database",

mixins: [React.PureRenderMixin],

render: function render() {

//(...)

}

//(...)

});

This is all that is necessary to realize gains in this case. If data is deemed unchanged, no further actions are taken to draw that branch of the DOM tree.

As we did for our previous set of benchmarks, we used browser-perf to capture the differences. This is total run time of the JavaScript code:

Grab the full results.

Aside: Immutable.js at Auth0

At Auth0 we are always looking at new libraries. Immutable.js is no exception. Immutable.js has found its way into our lock-next and lock-passwordless projects (lock-next, our next generation lock library, is still under internal development). Both of these libraries were developed with React. Rendering React components can get a nice boost when using immutable data due to optimizations available to check for equality: when two objects share the same reference and you are sure the underlying object is immutable, you can be sure the data contained in it hasn't changed. As React re-renders objects based on whether they have changed, this removes the need for deep value checks.

A similar optimization can be implemented in Angular.js applications.

Do you like React and Immutable.js? Send us your résumé and point us to cool projects you have developed using these technologies.

Conclusion

Thanks to functional programming, the benefits of immutability and other related concepts are tried and tested. Success stories behind the development of projects using Clojure, Scala and Haskell have brought a bigger mindshare to many of the ideas strongly advocated by these languages. Immutability is one of these concepts: with clear benefits to analysis, persistence, copying and comparisons, immutable data structures have found their way into specific use cases even in your browser. As usual, when it comes to algorithms and data structures, careful analysis of each scenario is required to pick the right tool. Considerations regarding performance, memory use, CPU-cache behavior and the types of operations performed on the data are essential to determine whether immutability can be of benefit to you. The use of Immutable.js with React is a clear example of how this approach can bring big benefits to a project.

If this article has sparked your interest in functional programming and data structures in general, I cannot recommend strongly enough Chris Okasaki's Purely Functional Data Structures, a great introduction to how functional data structures work behind the scenes and how to use them efficiently. Hack on!

Quiz

Can you answer the following 5 questions about immutability and functional programming in general? Find out!